Contents

Exercising their intellect

Freshmen learn about thinking from Nobel laureate

By Steven Schultz

Princeton NJ -- In their first academic lecture at Princeton, members of the class of 2008 learned some sobering information about the first-rate minds that they are setting out to expand.

''Mental effort, I would argue, is relatively rare,'' said Daniel Kahneman, professor of psychology and public affairs. ''Most of the time we coast.'' Kahneman reached those conclusions in his talk ''The Wonders and Flaws of Intuitive Thinking,'' which he gave for the annual Freshman Assembly Sept. 5 in Richardson Auditorium as part of orientation.

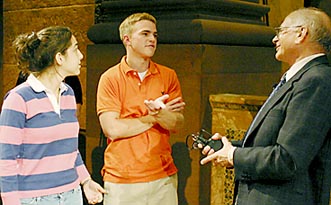

Freshmen (from left) Peri Rosenstein and Chris Nenno spoke with Daniel Kahneman after he delivered the annual Freshman Assembly lecture Sept. 5. Kahneman, who spoke about ''The Wonders and Flaws of Intuitive Thinking,'' said he was pleased to be ''ambushed at the door'' by students with questions after the talk.

The assembly is intended to introduce freshmen to the intellectual life of the University. The format follows the structure of many classes the students will encounter: a lecture followed by small discussion groups.

Kahneman, winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics for research on the nonrational, psychological side of decision-making, told students about two systems of human thought, intuition and reasoning, and showed how it is the former that guides much of our day-to-day activity. While intuitive judgments are critically important and are largely very accurate, they are tricked by illusions and can lead to overconfidence and illogical behaviors, Kahneman said.

Studies have shown that when people say they are ''99 percent sure'' of something, they tend to be wrong 10 to 20 percent of the time, Kahneman said in a talk that offered a window into current psychological research and served as a practical guide to critical thinking. ''This doesn't go away when you grow up. It doesn't go away when you grow old, and it doesn't go away when you become an expert.''

The power of suggestion

To illustrate his talk, Kahneman had given the freshmen an online survey that probed their intuitive thinking in advance of the lecture. Many of the questions were framed differently for half of the class than the other to highlight how answers changed according to how the question was posed. Others drew students into substituting intuitive guesses for reasoned estimates or calculations. (The questions and Kahneman's commentary on the answers are available at <www.wws.princeton.edu/~psrc/Survey4211.pdf>.)

For the first question, Kahneman asked students to write the last four digits of their telephone numbers and then asked if they thought the number of physicians in Manhattan was smaller or greater than that number. He then asked for an estimate of the number of physicians in Manhattan. The responses revealed that students with telephone numbers ranging from 0000 to 1999 made an average guess of 8,343 doctors, while those with numbers between 8000 and 9999 guessed 15,240 on average. The power of suggestion exerted by the phone number is called an ''anchoring'' effect, Kahneman said. ''Numerical judgments can be strongly influenced by almost any arbitrary number, if you consider it as a possible answer to a question.''

In another question, students indicated they were more likely to buy a $20 ticket to a show even if they had just lost a $20 bill than they would be to replace a $20 ticket if they had just lost it on the way to the show. ''Alternative descriptions of the same reality evoke different emotions and different associations,'' Kahneman said.

Savvy advertisers and negotiators often exploit such effects, Kahneman said.

He urged students to be aware of such illusions and avoid the perils of a ''lazy mind.'' ''I am recommending an active mind,'' he said. ''If it's important for you to get it right, when you recognize a situation in which you are prone to make a mistake, slow down and think. There really is no shortcut.''

In another survey question, the freshmen showed that they may already be following Kahneman's advice: ''A bat and a ball together cost $1.10. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?'' The intuitive answer is 10 cents, but a quick bit of algebra shows the answer to be 5 cents, which was the response of 78 percent of the freshmen who answered the question. In previous tests, just 52 percent of Princeton and Harvard students had been right, while MIT students had been 66 percent correct.

''You did better than any group we have seen so far,'' Kahneman told the students, evoking vigorous cheers. ''There are two possible explanations for this: One is that you are very, very smart. The other is that you were a little worried, and that you were paying attention more than the other people who have filled in this form. So we will find out over the next four years which is more likely to be the truth.''

After the talk, students joined their residential advisers in their residential colleges for precept-like discussion sessions. In a group in Mathey College, students quickly began thinking about how the ideas from the lecture meshed with their personal experiences.

One student said the lecture started her thinking about the presidential election and how issues and polling results are presented. ''It has so much relevance to almost everything in our lives,'' said another student, noting that even the Princeton meal plan has a default option that probably influences the number of people who choose it.

Other students raised the possibility of taking Kahneman's advice too far and over-analyzing matters that would have been more quickly or accurately addressed by first impressions. That conversation, in turn, prompted a discussion about the need to be intellectually flexible and to stretch one's thinking processes while staying true to important beliefs. ''It's important to make new ideas and remember what you had before,'' concluded one student. ''You need to keep recalibrating.''

top