Scientists learn more about ocean from schools of vehiclesSomething 'fishy' about work of underwater glidersBy Steven Schultz Princeton NJ -- In research inspired by the graceful coordination of fish schools, a team of Princeton engineers participated in a month-long robotics experiment this summer that involved launching fleets of autonomous underwater vehicles into the Pacific Ocean. The researchers tested the vehicles' ability to move in formation through the water while mapping ocean currents and tracking marine microorganisms. The work, sponsored by the Office of Naval Research, could yield benefits for a wide range of fields from climate and ecological research to military surveillance.

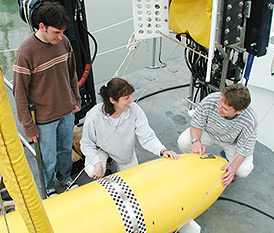

The project, called the Autonomous Ocean Sampling Network, took place in California's Monterey Bay and was the largest and most complex effort ever to test an entire fleet of autonomous underwater vehicles, while collecting real data about conditions under the sea. As many as 15 underwater gliders, each about six feet long and weighing more than 100 pounds, made coordinated sweeps through Monterey Bay, with some heading more than 25 miles from shore and diving to depths of 3,000 feet. The experiment was a multi-institutional collaboration involving a unique mix of biologists, ecologists, oceanographers and engineers. The Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute hosted and coordinated the experiment, which included 10 other universities and research institutions. The Princeton team, led by Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Naomi Leonard, was responsible for programming the gliders to move in formation while making their own decisions about where to go to collect the best possible data. "The gliders [were] out there foraging for information, looking for rich data that helps us understand ocean processes," said Leonard. The approach was inspired by the behavior of schools of fish, which could be seen as a coordinated network of sensors looking for the richest supplies of food, Leonard said. For many of the research groups, the experiment culminated years worth of individual efforts and tested their ability to mesh into a working system. "It's phenomenal," said Leonard after launching and monitoring one of the first groups of vehicles. "I am so impressed by what these gliders can do. They just stay out there like workhorses and run autonomously." The experiment was the first to attempt a system of immediate feedback in which the vehicles reported data to oceanographers and biologists, who used the information to make on-the-spot refinements to computer programs that simulate conditions under the sea. Those scientists then predicted how the ocean currents were likely to evolve and relayed their predictions to the robotics and control experts, who adjusted the routes and programmed behavior of the vehicles. The vehicles, in turn, tracked gradients of temperature, salinity or other features to find areas of interest and reported back increasingly targeted data. "There are so many dynamics in the ocean that we do not understand, and the dynamics of the vehicles themselves are not even certain," said Leonard. "So the feedback is there to provide robustness; it's a way to manage uncertainty." This network of autonomous sensors represented a major step forward in researching the dynamics of the sea, said Jim Bellingham, director of engineering at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute and the leader of the project. "If you don't use these underwater vehicles, you are really very limited in what you can learn about the interior of the ocean," he said. The best current techniques involve taking readings from stationary moorings or dragging instruments behind ships, but these often fail to zero in on the transitory shifts in currents and temperature that drive much of the ocean's ecology. "We're seldom in the right place at the right time," Bellingham said. Leonard said, "It's amazing that we now have these sensors out there that are so smart and so capable, and they are providing an enormous amount of data." The main phenomenon of interest in Monterey Bay is a plume of cold, nutrient-rich deep-sea water that rises toward the surface across the mouth of the bay. These upwelling events cause the plankton to "bloom," which supports the rich fisheries and other wildlife in the area. The underwater vehicles are engineering innovations on their own. They are essentially gliders because they have no propellers, thrusters or any kind of external propulsion system. Instead, they are equipped with pumps that take in or eject water, which makes the gliders sink or rise. As they go down and up, the vehicles glide forward aided by fixed wings. They steer with a rudder or, in some cases, simply by shifting their batteries from one side to the other, which makes the glider bank. This streamlined design requires a minimum of battery power and allows the vehicles to remain at sea for weeks at a time. The gliders surface every few hours to relay data, accept new instructions and check their locations using the satellite global positioning system. While underwater, they coordinate their locations with the help of an onboard compass and a device that measures their altitude from the ocean floor. The researchers already have begun planning a follow-up experiment for 2005. Additional participating research groups included: the California Institute of Technology, California Polytechnic State University, Harvard University, the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, the Naval Postgraduate School, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the University of California-Santa Barbara, the University of California-Santa Cruz and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. |

Contents |

|||||