|

Princeton

• Geowulf: Is this the future? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If a city is set on a height, living in that city will not be good."

So they believed in ancient Mesopotamia. That line is the first in a huge collection of omens compiled by Babylonians and Assyrians living in the area now known as Iraq, between approximately 1800 and 600 BC.

The collection is the subject of a book, If a City Is Set on a Height, written by Princeton Weekly Bulletin editor Sally Freedman and published by the University of Pennsylvania Museum this past spring. The book includes a line-by-line translation of some 1,600 omens in the collection, which is written in the ancient Semitic language Akkadian and known by its Akkadian first line as Shumma Alu ina Mele Shakin -- or Shumma Alu, for short.

Reference work

"Ancient scholars compiled Shumma Alu as a reference work," Freedman says. "It functioned as an omen encyclopedia -- except that instead of arranging the omens alphabetically as we would, they arranged them by topic."

There are categories such as omens that occur during the construction of a house (e.g., "If snakes coil in the foundations, the owner of the house will go to prison"); omens that appear in a completed house ("If fungus is seen on an exterior wall, a servant will die"); and omens associated with the digging of a well ("If a man opens a well in a garden, he will become rich").

Some sections include rituals to avert the threatened consequences of a particular omen. One, for instance, warns of the evil portended by stuck locks and broken doorlatches. Then it offers the following palliative: "You roast a spider from the wall, a gheefly, a moth and a scorpion; bray them together; and mix with the blood of a bat. Smear the door and handle seven times with the mixture, and the evil will be averted."

"Though we don't have any hard evidence of this particular ritual being enacted," Freedman says, "we do have evidence that Shumma Alu was consulted in the real world. For example, there's a letter to King Esarhaddon (c.670 BC) where the writer responds to a query about lightning striking a field and quotes verbatim three omens from the collection."

Forgotten for centuries

The omens Freedman studies lay forgotten for centuries. Inscribed on clay tablets, they were buried along with many thousands of other tablets -- all the written records of the Assyrian and Babylonian civilizations that came to an end in the first millennium BC. "As those civilizations were supplanted, first by the Persians and then by the Greeks, their writing system and even their language died out, until virtually all knowledge of them was lost," she says.

The civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia were rediscovered in the 19th century, when European archaeologists began digging in Iraq. As the written records were unearthed, they made their way to the museums that financed their recovery, and the laborious process of decipherment and translation began.

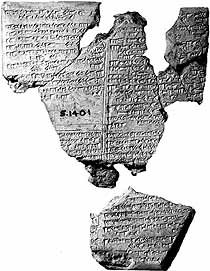

There are hundreds of thousands of Mesopotamian documents in various museums, Freedman says. They are written in wedge-shaped characters known as cuneiform, incised with a stylus on clay tablets that range in size "from a postage-stamp to a mousepad. These texts represent all the genres of a literate culture. They include everything from tax receipts to personal letters to legal contracts to medical prescriptions to epics to hymns -- to omens."

The texts relating to omens are surprisingly numerous. They comprise "fully 40 percent of scholarly and scientific texts (as opposed to economic and administrative records)," Freedman says, citing an estimate by the late scholar A. Leo Oppenheim. "The Mesopotamians derived omens from many sources," she continues. "The three most important were astronomical events, the livers of sacrificial animals, and the occurrences of everyday life -- the last being the theme of Shumma Alu."

10,000 lines

"Shumma Alu was a big series. It included more than 100 chapters, ranging in length from 30 lines to more than 200. The total probably amounted to some 10,000 lines. And because it was considered important, there were lots of copies of the collection in antiquity."

Then came the destruction of Mesopotamian civilization and the vicissitudes of 2,500 years.

"We now have no complete copy of Shumma Alu," Freedman says. "We don't even have complete versions of any given chapter. What we do have, in various museums, are hundreds of fragments of an unknown number of copies from different locations and time periods. I try to piece those fragments together to reconstruct as complete a version of the original as possible."

This involves both physical and intellectual reconstruction, Freedman notes. "Many of the original clay tablets were broken when ancient library shelves collapsed or when 19th-century archaeologists shoveled them out of the ground. I've spent a lot of time in the British Museum with trays of fragments, piecing them back together like broken pots."

But many fragments don't join anything. "The rest of a text may be in another museum, or still unexcavated, or smashed to powder. That's where the 'intellectual reconstruction' comes in. As a puzzle, it can be totally absorbing. You have a segment of text. You find another fragment that preserves a few of the same lines as the first text, plus some lines that were broken away on the first text. Segment by overlapping segment, you build up a reconstruction of the original."

In this way, Freedman thinks it will be possible to piece together about 70 percent of the complete Shumma Alu. The book just published contains the first third.

Critical concern

The enormous number of surviving omens and omen-related texts indicates the importance of divination in the lives of the ancient Mesopotamians, Freedman says. "Augury was a critical concern not only of the scribes, who were interested in divination as a scholarly discipline, but also of the many individuals who observed omens, worried about them, consulted diviners about them and paid for rituals to protect themselves."

Part of the satisfaction of her study is "getting into the minds of those long-ago people, finding out a little about how they thought. Sometimes you find things that are startlingly familiar -- like the 'omen' where a black cat crosses someone's path -- and I feel a kind of continuity in the human condition. Those people were thousands of miles and thousands of years away from me, but there's still a connection."

In addition to editing the Bulletin, Freedman teaches Akkadian at Princeton Theological Seminary. After graduating from Brown and spending a year in Israel, she earned her PhD at the University of Pennsylvania, where she then spent several years working on Shumma Alu as a research fellow. Supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, she traveled regularly to the British Museum in London, where most of the Shumma Alu tablets are located. Since joining the Communications Office in 1983, she has continued to devote much of her free time to completion of the work she began as a graduate student.

"When I start something, I like to finish it," she explains. "And now there's Volume Two."