Startup companies

New patents, licensing policy permits Princeton to accept equity for granting rights

By Justin Harmon

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Many of the technologies disclosed to our office are very early-stage," says John Ritter, director of patents and licensing. "A startup company is often the appropriate vehicle for transferring the technology to industry."

A startup venture typically does not have sufficient cash to pay the owner of a patent for licensing rights. Thus, it makes sense to seek an equity position in the company in lieu of an up-front payment, according to Ritter. However, before last year the University had no institutional policy that would allow the Office of Patents and Licensing to accept equity as consideration for granting rights to Princeton-owned patents. The new policy was approved by the University Research Board last year.

Quorum Pharmaceuticals

A recent startup involving a research breakthrough by Assistant Professor of Molecular Biology Bonnie Bassler illustrates the possibilities. Bassler and Michael Surette of the University of Calgary found a gene that many bacteria, including dangerous ones such as E. coli and salmonella, use to sense whether they are part of a dense or sparse population.

Because some bacteria emit disease-causing toxins only when their population reaches a certain size (a quorum), blocking this gene could inhibit the production of toxins. The gene could thus become a valuable tool to drug developers looking for new ways to combat bacteria that are becoming increasingly resistant to current treatments.

Because Bassler was about to publish a paper describing the discovery, Princeton initially filed for a provisional patent on the gene research. The University of Calgary, coowner of the patent, cooperated in the filing. A startup company, Quorum Pharmaceuticals Inc., was incorporated in February specifically to pursue the technology, and Princeton has granted a license option to it. Quorum's founder, Jeff Stein, formerly principal scientist at Diversa Corp. and currently a faculty research associate at the University of California at San Diego, had worked with Bassler before she came to Princeton.

The license with Quorum will require the payment of an advance license fee, maintenance fees and a royalty rate against net sales, as well as consideration for nonroyalty sublicensing revenues. Quorum assumes responsibility for all patenting costs and must meet fundraising milestones over the 30-month period following the signing of the agreement.

The license will provide an equity share in Quorum, and all of the consideration received will be divided between Princeton and the University of Calgary. According to Princeton's equity policy, Bassler's portion of Princeton's equity share in the company will be issued to her directly.

Inventor retains oversight

Licensing to a startup enables an inventor to retain some oversight of ongoing research, without necessarily maintaining an active research role. More frequently, licenses are issued to established companies, which often fund continued research in the inventor's own lab.

"I didn't want to license the work to an existing company," says Bassler. "I wanted to be involved in an ongoing way. I advise Quorum and consult with them. On the other hand, there are no research grants that come back from Quorum to me or to Princeton. I want to work on the fundamental questions that interest me and to do so at the pace that seems appropriate to me scientifically. I want my graduate students to be as creative as they can be and to have no goals that aren't very abstract. The company has to work faster than that."

The Patents and Licensing Office "did a good job protecting my interests," says Bassler. "They took enormous care."

The patenting and licensing process is labor-intensive, Ritter says, and faculty have to maintain active involvement, particularly in the case of a startup. The process of identifying potential licensing partners often begins with a faculty member's ideas of what industries pursue related technologies and in many cases with their own contacts. Ritter supplements any faculty-generated contact lists using a variety of literature and Internet resources. His office then initiates contact with these companies and follows up on individual leads.

One benefit of the process, Ritter says, is that it can expose faculty to new industry contacts, who may then take an active interest in their research. It is not uncommon for such contacts to yield research grants, even if initially no license to the patent ensues.

Disclosure leads to discussion

Will Happer, professor of physics and chair of the University Research Board, is himself an inventor with technology licensed through Princeton, and he recommends that faculty contact the Office of Patents and Licensing when they have research breakthroughs.

"I think that any time a project yields results that look interesting, it's in the interest of the faculty member to file a disclosure form," he says. "Then the professionals can sit down with the faculty member and see whether it might be worth filing a provisional or regular patent application."

Relatively new to US patent law, provisional patent applications allow filings to be made without the detailed claims that become the "legalese" of the patent, according to Ritter. As long as a filing describes the invention well enough that it could be reproduced by "one skilled in the art," it establishes a priority date for the inventor's claim. "Provisional filings have become particularly important in academic settings, where there's often not enough time before publication to fully evaluate the patentability and commercial viability of a technology," says Ritter.

After a provisional filing, subsequent filings stake out the inventive claims and establish legal rights to the technology. Ritter works with faculty to ensure that patent filings are timed so as not to interfere with any publication of the research. Moreover, the terms of any license granted by the University always protect the rights of faculty to use an invention for their own research purposes, Ritter says.

|

|

|

|

|

|

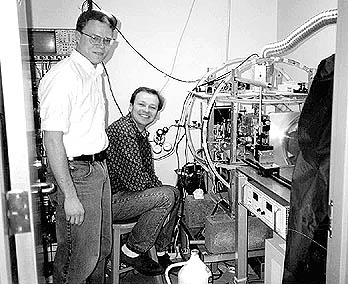

Happer's own patent is held jointly with Professor of Physics Gordon Cates, some of their former graduate students, and collaborators from the State University of New York at Stony Brook. It followed from a breakthrough in the design of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology. The researchers discovered a way to use laser-polarized xenon or helium gas to produce significantly finer pictures of human lungs and other body cavities.

On the basis of their invention, Happer, Cates and other partners founded Magnetic Imaging Technologies Inc. (MITI) to pursue further research on the technology under license with Princeton. MITI employed three former Princeton students who had assisted Happer and Cates in the lab. The international health care company Nycomed Amersham recently bought MITI.

"Our former students all were major option holders, so their net worth went up a bit," Happer notes. MITI's employees continue their development work near Duke Medical Center in Durham, NC, which is a major site for clinical trials, along with the University of Virginia at Charlottesville. "There is a little nest of Princetonians at the University of Virginia who have created the world center for gas imaging with our technology," says Happer. The leaders are a thoracic surgeon, Dr. Tom Daniel '60, and the chair of the radiology department, Dr. Bruce Hillman '69.

Meanwhile, Happer and Cates continue their own work on the physics behind the technology. "The fundamental physics is still interesting, and there are puzzles that need to be resolved," Happer says. "If we learn anything the company would like to run with, they can negotiate terms with us."

And MITI pursues its own research. "They're very good. We trained them, after all!" Happer notes.

In addition to Quorum and MITI, Ritter has a number of other licenses to potential startup companies on the horizon. Moreover, he says, faculty interest in all aspects of patenting and licensing activities is increasing. In the past fiscal year, his office received more than 60 invention disclosures, filed more than 50 patent applications and had 26 patents issue. The University's income from the program totaled $2.6 million. Fourteen collaborative agreements were executed. Research funding tied to these license agreements will amount to over $2 million over the next five years.

Though these numbers are considerable, "We don't promise to make millionaires," Ritter says. "We do provide a service to faculty and students."

top