Contents

Hopkins selected as architect for new chemistry building

By Ruth Stevens

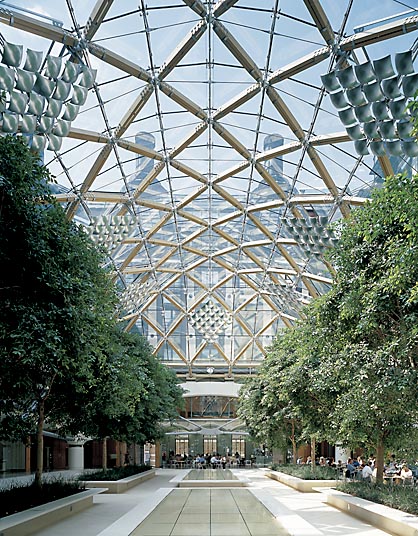

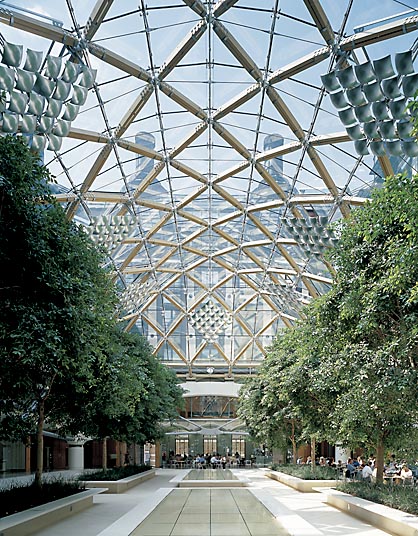

One of the best-known projects by Hopkins Architects is an office building for the Houses of Parliament in London. Located on the Thames between Parliament and Downing Street (to the right of Big Ben in the photo), it features a glass-roofed atrium courtyard.

Princeton NJ -- Michael Hopkins and his London-based practice, Hopkins Architects — a leading pioneer in British architecture — have been selected to design Princeton’s new chemistry building and its surrounding neighborhood.

“We wanted to choose architects who could design an excellent science building, and who are growing in prominence,” said Mark Burstein, vice president for administration. Hopkins has worked extensively in England, including completing projects in several academic settings. The practice recently began designing two buildings at U.S. universities.

Hopkins Architects, established in 1976, is a prominent architectural firm in the United Kingdom. Its designers have earned numerous awards for their work, with Michael and Patty Hopkins, his wife and partner in the firm, winning the Royal Institute of British Architects Royal Gold Medal and Michael receiving a knighthood in 1995. The company is known for its innovative approach to construction and its energy-efficient designs.

“Hopkins’ office building for the Houses of Parliament in London is one of their most well-known works, situated on the Thames between Parliament and Downing Street,” said Jon Hlafter, University architect. “With extensive use of glass and metal panels, it is a high-profile building on a high-visibility site. A glass-roofed atrium courtyard is not visible from the exterior but forms the heart and soul of the composition.”

The office building, called Portcullis House and completed in 2000, is built on top of a subway station, requiring the six-story structure to be supported by only six columns and the massive concrete arches that connect them.

Hopkins also has completed designs for universities in England, including the Queen’s Building, a three-story auditorium at Cambridge, and the Jubilee Campus for the University of Nottingham. The practice’s combination of clean design and energy-saving construction at Nottingham attracted the attention of two American universities: Hopkins has been selected to design an applied research facility at Northern Arizona University and a new building for the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at Yale.

“The Hopkins office is substantially ahead of most American firms in the conceptual design of sustainable buildings that use natural ventilation and passive solar techniques,” Hlafter said. “We hope and expect that we will apply that design orientation to our chemistry laboratory — potentially the greatest energy consumer on the campus.”

Hopkins’ unusual approach to design is also what attracted Princeton, according to Burstein. “Much of the time, architects work from the outside in. This firm works from the inside out. One of the unique attributes of a chemistry building is the importance of what’s called building systems because of the experimentation that takes place. The way Hopkins approaches design is to start with the program needs first, then create a building façade from the program needs.”

Over the next several months, the architects will meet with faculty members in the chemistry department to define the program for the new building. Encompassing 200,000 to 300,000 gross square feet, the facility will be constructed on the site of the Armory on Washington Road, moving the chemistry department south from its current home in Frick Lab and closer to the facilities for physics, molecular biology, genomics and other science departments. Construction is expected to begin in two or three years and to be completed in five years.

“It’s a real honor to be selected by Princeton to design a building on that beautiful wooded site,” Michael Hopkins said. “It will be the first Princeton building that you will see through the trees as you approach the University heading north on Washington Road, so we shall be giving it our best efforts. At this particular moment in the development of scientific research, a state-of-the-art chemistry building next door to physics provides the opportunity of not only making a building of technical excellence, but of making a truly open and flexible building which encourages contact and interaction both within the discipline and across the scientific disciplines.”

Hopkins will collaborate with Payette Associates, a nationally renowned architecture firm based in Boston that has done previous work on the Princeton campus. The firm, whose specialties include the design of complex buildings for scientific research and teaching, has been involved in design work for the Lewis Thomas and Schultz labs and for an addition to Frick in the 1980s. Payette Associates also helped produce a feasibility study several years ago for a chemistry facility that will be revisited as part of the design process for the new building.

According to Robert Cava, professor and chair of chemistry, the 76-year-old Frick Lab is one of the oldest functioning chemistry facilities at an academic institution in the United States. “The nature of science — and chemistry, in particular — has changed much in the last 80 years,” he said.

Cava is enthusiastic about a new building that both meets today’s technical standards and promotes more interaction among faculty and students, noting that Frick has no common places in which to “create an intellectual community.”

“The new design will allow us to fully integrate our teaching program with our research program,” he said. “And being in close proximity with the other sciences will help us to develop even stronger collaborative ties to those programs.”

Burstein said that another of Hopkins’ strengths is creating spaces that promote interaction. “We wanted to choose architects who could understand the technical needs of a complicated research building but also provide a space that would be very attractive to faculty as a work environment,” he said. “Hopkins’ Parliament building has warm and welcoming work spaces but also very clean and thoughtful public spaces.”

The new chemistry building is part of an effort to consolidate a “science neighborhood” that also would incorporate Fine, McDonnell, Jadwin and Peyton halls and the Frank Gehry-designed Lewis Library, which will be completed in 2007, on the same side of Washington Road as well as the Lewis Thomas, Schultz, Moffett and Icahn labs and Eno and Guyot halls on the other side of the road. A new pedestrian bridge will connect the two sides.

In addition to designing the building, Hopkins Architects will be responsible for crafting the neighborhood. “One of the challenges of the site is that Jadwin Hall has its loading dock on its southern side, which will likely be across from the entry point of the chemistry building,” Burstein said. “Hopkins will be charged with sorting that out as well as other circulation issues, such as linking the bridge into the project.”

top