|

|

|

|

|

|

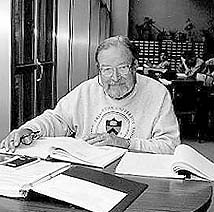

Henry Callahan (Photo by Denise Applewhite) |

Most days you can find Henry Callahan at the back of the E-Quad library, laboring over a problem set.

This semester the course he struggles hardest with is Civil and Environmental Engineering 462, Design of Large-Scale Structures: Bridges.

It's a typical undergraduate experience, except that Callahan is no typical undergraduate. He is 83 years old. While it is common to see senior citizens auditing Princeton classes, Callahan is one of just two octogenarians taking courses for credit through Princeton's Continuing Education.

Callahan's counterpart in the humanities is Anne Martindell, 85, who is taking Princeton courses to fulfill requirements for completing her degree in American Studies at Smith College.

"'It's Never Too Late' is the working title for my memoirs," she says.

That's a philosophy Martindell and Callahan live by, but both have found that reentering an academic system they left more than 60 years ago is a serious challenge.

Bobby sox to body piercing

Martindell was enrolled in Smith's Class of 1936, but she left after two years because her father feared that her intellectual pursuits would interfere with her marriage prospects.

Now with 17 children, grandchildren and greatgrandchildren, and a rich career in public service, Martindell is due to graduate with the Smith Class of 2002. Though Smith requires that she spend two semesters on campus to complete her degree, she is taking other classes closer to home in Princeton. Last year she studied the Civil War with Davis Professor of American History James McPherson, and this semester she is taking Politics Professor Paul Sigmund's course on Conservative Political Thought.

Martindell says that when she resumed life as an undergraduate, the first differences that struck her were superficial ones: the girls' uniform of flannel skirts, bobby sox and saddle shoes had been replaced by jeans, tee-shirts and body piercing.

Study habits had changed too, as she discovered when she participated in class discussions via e-mail. "I get e-mails sent 3:14 in the morning," Martindell says. At Smith in the '30s she was considered something of a night owl because she would stay up until 11 or 12 when her roommate wanted to go to bed at 10. "I would go into the bathroom and sit in an empty tub with a light hanging down so I could read."

|

|

|

|

Anne Martindell in Firestone Library (Photo by Denise Applewhite) |

|

New standards of personal freedom, Martindell noticed, have come along with a shift in intellectual standards. Then, "We didn't do much independent thinking," she recalls. "We were told what to think, and we were told to parrot it back to our teachers. Intellectually, the students now are much more mature than we were." And a great deal of emphasis is placed on independent analysis of the course material. "It's been very difficult to adjust."

Martindell has a wealth of personal experience to bring to bear on such analysis. She served terms as a NJ state senator before becoming director of the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance under the Carter administration and then serving two years as US ambassador to New Zealand.

As a lifelong Democrat and an "active liberal," she took Sigmund's class, she says, "because I thought it would annoy me" and jumpstart critical thinking. Now she is surprised to find herself agreeing with some of the reading, particularly the idea that "along with independent thinking has been an erosion of some kinds of standards.

"So I'm learning not just the facts, but a new way of thinking," says Martindell.

Slide rules to computers

Callahan has also been challenged by new ways of teaching. After graduating in 1939 from the University of Pennsylvania with a bachelor's degree in chemical engineering, he spent most of his career at American Cyanamid, working his way from research chemist to manager of engineering operations for Europe, the Middle East and Africa before retiring in 1982.

After his wife died in 1997, Callahan started coming from his home in Westfield to audit classes at Princeton. One of them was Structures and the Urban Environment, taught by Wu Professor of Engineering David Billington, which sparked his interest civil engineering.

"It just occurred to me that it would be an awful lot of fun to study it in more detail and find out what these other engineers were doing," he recalls. Not content with auditing, he wanted to get a master's degree, and Billington helped him map out a program of courses.

Not at all awkward

Callahan has now taken about five courses, but his experience has made him rethink his quest for a master's. Two major changes in modern engineering -- the heavy use of computer technology and the importance of high-level math -- have been stumbling blocks, he says.

"I went through my professional life with a slide rule in my hand," he says. And at Penn the highest level of math he studied was calculus, while today no engineering undergraduate comes to Princeton without having studied calculus in high school.

Billington, who graduated from Princeton in 1950, says he is sympathetic to Callahan's difficulties. "If I were coming in now and taking courses, I'd be in trouble," he acknowledges.

Nonetheless, Callahan has found the chance to work with undergraduates richly rewarding. "It's been fun and not at all awkward," he says. "They are a nice bunch, and a smart bunch."

"We've enjoyed having him," says Billington, "and he's really added something to the classes."

Despite his difficulties with math and computers, Callahan says his experience as a student has been worthwhile. "I know more than I did before," he says, "and that's progress."

top