|

|

|

|

|

|

Jonathan Cohen shows future site of

functional magnetic resonance imaging

|

By Steven Schultz

Sitting in the doctor's office when he was 11 years old, Jonathan Cohen picked up a copy of Life magazine and became engrossed in a story about the exploding pace of neuroscience research.

"I remember thinking 'Wow, the great frontier of science is not out there in the stars, it's right here with me in my head."

Three decades later, brain research is indeed a frontier of science, and Cohen, professor of psychology, is at the center of it. He came to Princeton in 1998 to become director of the new Center for the Study of Brain, Mind, and Behavior. As its weighty name suggests, the center is an ambitious effort to investigate some of the most elusive and quintessentially human aspects of our being.

The center's goal is to understand the biological parts and processes behind such phenomena as consciousness, moral behavior and logical thought.

"There are more synapses in the brain than stars in the galaxy," Cohen notes. "We are studying the most complex device in the known universe."

Tracks converging

For many years, brain research moved along separate tracks. Cognitive psychologists probed behavior and experiences of the mind, while neuroscientists investigated the physical properties of the brain. Now advances in various areas are allowing scientists to bring the two tracks together. The emerging field of cognitive neuroscience aims to reveal the physical processes that give rise to the experiences of the mind.

"Now we're getting to the nuts and bolts of the parts of the brain that make us who we are," says Joshua Greene. A graduate student in philosophy, he has begun a study to reveal biological underpinnings of certain types of moral behavior.

Quantitative techniques

The joint exploration of physical and mental phenomena accelerates a trend toward using rigorous quantitative techniques to explore areas of psychology that were previously limited to introspection and qualitative description, says Cohen.

The ability to take these steps builds on research both in and outside of psychology. The Brain, Mind and Behavior Center has affiliated faculty in molecular biology, applied mathematics, engineering, computer science, physics, chemistry, linguistics and philosophy, as well as scientists from Rutgers University, University of Pennsylvania and Lucent Technologies.

|

|

|

|

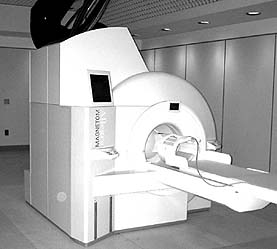

fMRI scanner

|

|

Such machines are used frequently in diagnosing and studying injuries and illnesses but are not widely available to scientists doing basic research. Although two other schools have followed Princeton's lead, Princeton was the first non-medical school to commit to building a human brain-imaging center, says Cohen.

The $2 million scanner is scheduled to begin operation this coming fall in Green Hall. It will be twice as powerful as standard medical fMRIs, making it among the most powerful in the country, says Cohen.

For Greene, access to fMRI creates research possibilities that were previously unimaginable. His experiment, a mix of ancient and modern probes into the human psyche, involves presenting a set of classical ethical dilemmas to subjects who are undergoing fMRI scans and then looking to see what parts of the brain are engaged during moral decisionmaking.

Greene has proposed that not all moral decisionmaking is the same. Some moral decisions, he argues, are produced in an "abstract" or "cognitive" way, while others are driven by emotional response. The scanning experiment will compare activity in brain areas known to be associated with logical reasoning and activity in areas associated with emotion.

If different kinds of moral questions produce dramatically different patterns of brain activity, that will suggest that "the innate functional organization of the brain, and not just the things we've learned from experience, shapes our moral thought in surprising ways," Greene says.

Collaboration with hospitals

In addition to yielding fundamental insights into the brain, the center's research could shed light on neurological and psychological illnesses. Cohen, for example, is studying a part of the brain that appears to monitor for conflicting situations that vie for attention. How we direct our thoughts in the face of conflict is a key question in psychology, and the loss of that ability is a defining characteristic of schizophrenia, says Cohen.

Cohen says the center will seek to collaborate with hospitals in New York, New Jersey and Philadelphia. Although most of his work is basic research, Cohen is no stranger to clinical research. He holds an MD from the University of Pennsylvania as well as a PhD in cognitive psychology from Carnegie Mellon University. Before coming to Princeton he held joint appointments at Carnegie Mellon and the University of Pittsburgh. He has retained his appointment at Pittsburgh and continues to do some clinical research there.

Link with Genomics Institute

Cohen is not the only new person associated with the center, which is participating with several academic departments in the recruitment of faculty. Two assistant professors with interests in neuroscience, Michael Berry and Sam Wang, have joined the faculty in Molecular Biology, and assistant professors of psychology Frank Tong and Sabine Kastner will start in the fall.

Cohen says that a long-term goal for the Brain, Mind and Behavior Center will be to link its work with that of the Institute for Integrative Genomics directed by Shirley Tilghman, Howard A. Prior Professor in the Life Sciences.

"One of the remaining great frontiers in science is a better study of who we are," Cohen believes, "and what that really comes down to is our genetics and how our brain functions."

But building the connection between genes and the mind is a slow and difficult process, one Cohen likens to construction of the Golden Gate Bridge. "We've started to build out from both sides and are even building the two towers; there are boats going back and forth right now; but the bridge is not done."

top