"These guys are aces"

Physics machine shop makes everything to order, from satellite parts to bell clappers

|

|

|

|

|

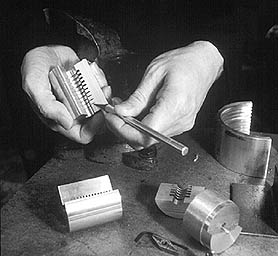

Feed horn has "533

exquisitely precise rings cut into its inside

surface." (Photo by Denise Applewhite)

|

One Wednesday afternoon in February, the folks down at NASA were having trouble.

For months Princeton physicists had been working with NASA engineers to prepare for the launch of a satellite. Delicate instruments, designed to probe for the faintest echoes of the Big Bang, were in their final round of tests in a chamber that simulates the brutal cold of space.

Suddenly it became clear that one part of the assembly was running too warm compared to the rest. In space, the problem could ruin everything. The offending part was buried so deep in the instrument that no one could see it. The scientists decided they could use mirrors and small tools to thread a complicated copper strap into a hidden cavity where it would siphon away heat. The strap would need to be perfect--thick enough to carry the heat but flexible in just the right places.

The question was: Who could make the strap, make it perfect and make it now? For all involved, there was only one answer: the Princeton Physics Department machine shop.

Cutting edge

The sureness of that answer is one of the hidden stories of the Physics Department and something that many faculty members say they rely upon to maintain their place at the cutting edge of science. As David Wilkinson, Cyrus Fogg Brackett Professor of Physics, summed it up: "These guys are aces."

From the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, MD, a chief NASA engineer faxed some drawings of the satellite problem to Professor of Physics Lyman Page. Page went down to the ground floor of Jadwin Hall and had a quick conversation with Laszlo Varga, foreman of the machine shop.

Days later, the strap was in Maryland. "It fit; they ran the test; it worked perfectly," says Page. "It was just great."

|

|

|

|

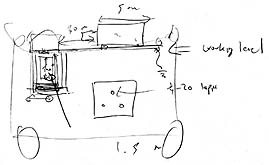

Sketch of "cart with lasers,"

submitted to the machine shop by Albert Young,

assistant professor of physics

|

|

Last year NASA awarded the shop its International Support Award in recognition of its many contributions to the MAP project, as the satellite probe is called.

"They have world-class talent there in the Physics Department shop," said Chuck Bennett, principal investigator for the MAP project at Goddard. "We at NASA are really grateful and impressed with the superb quality machining. They are inventive and responsive. They are definitely can-do people."

One-on-one conversations

Varga came to the United States from Hungary in 1957 at the age of 20, having learned metal-working trades in a railroad car factory. After working several jobs, he settled in as a machinist for a small company in Edison. In 1968 a Hungarian friend saw a newspaper ad for a machinist at Princeton, and Varga drove down to help his friend fill out an application. He had no intention of moving himself, but when he was offered the job instead of his friend, he decided to take it. He still commutes from Edison.

William Dix (l), Laszlo

Varga, Theodore Lewis and Glenn Atkinson (Photo

by Denise Applewhite)

It quickly became clear that Varga was not only a

very skilled machinist, but he had an uncanny ability to

grasp what the scientists needed. He developed a casual

working relationship that dispensed with formal drawings and

specification sheets in favor of one-on-one conversations

and hand-drawn sketches. As foreman Varga has nurtured

similar qualities in the main people who work with him,

technical staff members William Dix and Glenn Atkinson.

"You save so much time, and it opens so many possibilities if you can walk downstairs and just talk with them, instead of having to work up a whole technical drawing," says Page.

Bell clappers to boiler parts

This combination of easy style and hard results keeps the shop in heavy demand. In recent years the shop has developed instruments for half a dozen high-altitude balloon experiments, built telescopes (including one Varga personally helped install at the South Pole) and made countless other instruments.

It also cooperates with the several other technical facilities in the Physics Department, including the Elementary Particles Lab, a similar shop that builds detectors for particle accelerators and other experiments.

The need for good machining at the University is not limited to high science. The shop has made everything from clappers for the Nassau Hall bell to custom window screens for the Graduate College.

Recently Dix was machining a solid brass ornament for the top of a railing that was undergoing repair.

"One minute we could be working on a boiler part, and the next we're drilling a 15,000th-of-an-inch hole," he said.

Impossible is interesting

These technicians don't find a job really interesting until it seems impossible.

"You come to a point in every project where you have to sit down and say 'Holy smoke, How are we going to do this?'" says Varga. "Then we sit down with the professor, and we find a way to do it."

That was the case with the "feed horn," a lightweight aluminum cone that funnels microwave radiation into the heart of the MAP detector. The cone, about 30 inches long, needed to have a sequence of 533 exquisitely precise rings cut into its inside surface. Reaching a tool deep inside a tight space, then making cuts without letting it chatter or slip is an enormous challenge.

"When you cut one of these horns open and look at it, it seems unbelievable that you could make something like this," says Page. "It's just astounding, and these guys made two dozen of them."

When the MAP satellite is launched later this year, the feed horns will provide data that scientists hope will go a long way toward explaining both the history and fate of the universe. For the people in the shop, that's the payoff.

"It's very satisfying to know that what we made was used and that they got very good data from it," said Atkinson.

top