Ancient World: a pretty big place

By Caroline Moseley

|

|

|

|

|

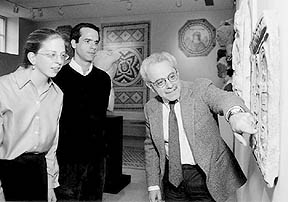

Graduate students Emily

Mackil (l) and James Woolard with Robert Kaster

(Photo by Denise Applewhite)

|

"The Ancient World is a pretty big place," says program director Robert Kaster, who is Kennedy Foundation Professor of Latin Language and Literature. "It covers a lot of territory, a lot of time -- and crosses a lot of traditional disciplinary boundaries. There are students and faculty interested in various aspects of the Ancient World or who approach it from different angles, and they have a lot to say to each other. The Program in the Ancient World gives them that opportunity."

Classics graduate student Emily Mackil agrees: "The value of our program gatherings lies in the exchange not only of information but of different approaches."

What are the temporal and spatial parameters of the Ancient World, as studied at Princeton?

"Predominantly, we mean the ancient Mediterranean world," Kaster says. "Areas within a certain distance of the Mediterranean coast are also fair game for the program: Greece, Rome, Egypt, the Near East. Greece," he adds, "tends to be the point around which most, but not all, students' interests pivot in one way or another."

In terms of time, "We're talking roughly about the age of Homer -- let's say the eighth century BCE -- to the 12th century of our own era." As in many graduate programs, the parameters tend to be established by the interests of the faculty.

Always a center of interest

There are about 30 students in the program this year, which Kaster says is typical. "The Ancient World is not what you'd call trendy, because it's always been a center of interest -- you can't get away from it. First, because the modern world takes so much from the ancient. Second, because the ancient world is so different from the one in which we live -- it's hard to understand where we are culturally, historically or socially, if we don't know where we were.

"For example, it is inconceivable to try to make sense of the modern West without understanding Christianity -- regardless of personal religious beliefs. And how can we understand Christianity without knowing something of its origins, in a specific place at a specific time -- which happens to be the ancient Mediterranean world?"

Similarly, Kaster points out, "Our notions of democracy and political philosophy, our values and ethical systems, originate there."

Still, he continues, "because the Greeks, Romans and other inhabitants of the ancient Near East were not us, studying the ways in which we are different helps us understand our own lives."

Shame ancient and modern

A case in point is shame -- the subject Kaster discussed in a public lecture on Alumni Day entitled "Emotions and Ethics: Shame Ancient and Modern."

"There are certain ways in which the Roman idea of shame and ours are alike," he says. "Both have to do with evaluations of yourself in relation to how you see yourself being seen by others. At the same time, there are significant differences between the two notions of shame."

For us, he says, it is quite possible to feel shamed "by things over which we have no control, for which we accept no causal responsibility. We may be ashamed of being ugly; we may be ashamed of our parents.

"That would make little sense to a Roman. A Roman would not ordinarily express shame for something for which he had no personal responsibility. He would, on the other hand, be ashamed if he failed to perform a duty he felt obliged to perform."

Further, Kaster says, "In our society, I can put you to shame or shame you into something. There is literally no way of saying that in Latin."

Equally valued resources

The interdisciplinary nature of the Program in the Ancient World gives students an opportunity to examine issues that might not otherwise find a departmental home. Among current dissertation topics are friendship and other forms of social relations among women in Roman society, and Jewish liturgy and synagogue life in the first three centuries of the Common Era.

Elizabeth Greene, a fourth-year Classics student, is using ancient Greek literature and iconography to explore "the speeches, participants and performance of the departure ceremony that occurs when a warrior or traveler leaves a community, either to embark on adventures or to return home." The Ancient World program, she says, encourages an approach in which "neither text nor art receives a privileged status, but both serve as equally valued resources."

Third-year student Mackil is studying the origins and growth of federal states in three areas of Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. Making use of survey archaeology, epigraphy (reading ancient inscriptions) and numismatics (the study of ancient coins), she will try "to shed light on a corner of Greek history that has been left rather dim using the traditional methods of ancient history, which rely only on literary texts supported by a few inscriptions." She adds, "Seminars I have taken in the Religion, History and Classics departments have all influenced my thinking."

Roman festivals

To participate in the Program in the Ancient World, graduate students must satisfy requirements of their home departments and in addition, those of the program. Program requirements include an annual seminar -- this year it was a fall semester course on Roman Festivals of Spring and Autumn, given by Professor of Classics Fritz Graf. Such a topic, Kaster points out, "has interest for anyone in the program, as well as almost anyone in the social sciences and humanities."

There are two other requirements, Kaster says. "Students must have some experience in material culture -- that is, some aspect of the Ancient World that is not dependent on texts. Typically, that would mean working on an archaeological excavation in Greece or the Middle East." And there is a methodology requirement. Students must develop some competence in applying a particular method of study or analysis, such as epigraphy or numismatics, to ancient materials. At least one member of each student's dissertation committee must be from a department other than the student's home department.

Most presentations sponsored by the program are open to the public. There is a series of free public talks and seminars throughout the year; topics have included "Black Sappho," "Cleopatra and Her Impact on Rome" and "Was Homer Jewish? Ethnicity and Culture in the Graeco-Roman World."

Many events are in the format of Ancient World Brown Bag lunches. This may conjure up images of hempen sacks and hunks of unleavened bread, but Kaster says it's nothing so picturesque. However, he notes, "we do serve -- and eat -- a lot of cookies."

top