Play addresses school violence

By Marilyn Marks

|

|

|

|

|

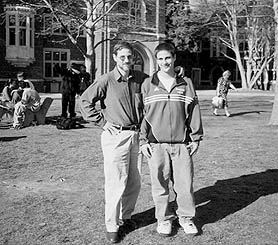

Robert Sandberg (l) with his

son, Eric Sandberg-Zakian (Photo by Denise

Applewhite)

|

Two boys had not killed a teacher and four classmates in a middle school in Arkansas, and a first-grader had not shot a six-year-old classmate to death in Michigan.

Nothing so dramatic was in Sandberg's mind in 1997 -- just the sight of kids jumping and pounding on each other when he went to pick up his seventh-grade son from middle school. He set out to investigate, interviewing children and teens in Princeton and Trenton. He wrote and rewrote. Two years later, Sandberg had his play, In Between, and the educational establishment, reeling from a series of school shootings, was ready to view it.

Sandberg is a lecturer in the Council of the Humanities and Theater and Dance Program. In Between is being presented at middle schools around the state by the George Street Playhouse in New Brunswick. Next fall, productions will be mounted in schools and theaters in Seattle and Houston.

And on April 5 the play will be featured as part of the 11th Annual Child Abuse Conference presented by the Dorothy B. Hersh Child Protection Center at Saint Peter's University Hospital in New Brunswick. Pediatrician Elizabeth Hodgson, comedical director of the center, said she hopes the play will prompt medical professionals and other community members to "think outside the box" on issues of childhood violence.

A girl named Cue

The play tells the story of a girl named Cue, a new kid at school who is caught between the school outcast and a clique of popular students with a bullying leader. Each time Cue comes to a moral crossroads, the actors play out the various actions she might take and their consequences. There's a hint of violence -- the outcast writes a poem that refers to "bodies on the floor" and "cold metal in my hands" -- but it all ends on a hopeful note.

Through his interviews with middle schoolers, the playwright said he began to understand the extent to which issues of popularity result in alienation and conflict on school campuses. He was surprised to find that most of the students he interviewed, including children from higher-income homes in Princeton, accepted confrontation as a necessary way to solve problems at school.

Among public school students from Trenton, that acceptance was even more marked, he said. "For many of these kids, there simply was no alternative to confrontation. It was an overwhelming thing in their lives."

Believing that adolescents would tune out any message they felt came from adults, Sandberg used in his play the words he heard in his interviews:

"This girl Ruth, she was always talking junk. When I put my hand up, everybody thought that I punched her. But I didn't punch her. I just went like that. I thought her crew was gonna be all over me, so I ran."

"In my old school, there was a kid like him. James. His locker was next to mine. He was from Austria or Australia or somewhere. One day, he just kinda went crazy. Some guys were crackin' on him and he jumped on one and started screamin'? The guys tore him off and stomped him."

Too real?

Sandberg's early drafts were a bit too real for the teachers and administrators who saw them. The first version of the play was called Done, and the central character was a student who got a gun and considered using it. In subsequent drafts, Sandberg toned down the language and revised the plot. At the request of administrators, he wrote in the character of a helpful, understanding teacher.

With these changes -- and the shock of the April 1999 deaths at Columbine Highschools began to open their doors to the performance, and the play has been touring on a busy schedule ever since.

Sandberg wants the play to be a catalyst for further discussion in the classroom and beyond. "I think there's a great desensitization toward these issues," he said. "I want the play the create an empathetic experience for the kids, so that when someone is about to be bullied or alienated, there's at least going to be some hesitation about accepting it."

Whether the play has had that effect, no one can know, but administrator Richard Cimino observed students' reactions when they saw the play at Bernardsville Middle School several weeks ago. They were quieter and more attentive than they usually are doing performances, he said, and "We had quite a few kids coming up to the actors when it was over to talk to them, which is not something we normally see."

23 plays produced

This semester Sandberg is teaching Princeton's introductory playwriting course. He has also taught freshman and junior seminars and an intermediate acting class and been a preceptor in two Shakespeare courses.

A member of the Class of 1970, he has graduate degrees from Wesleyan University and the Yale School of Drama and has been a playwright, director and teacher since 1972. Twenty-three of his plays have been presented professionally, and he has directed more than two dozen productions ranging from Euripides to Brecht to contemporary premiers.

He is now working on a version of the play for an adult audience, using the original title, Done. It will contain stronger language and overt sexual situations. The character who obtains a gun will be more central. And there will be no friendly adult to help the student find a way out.

top