Princeton Weekly Bulletin May 10, 1999

"Existential oomph"

Cross-disciplinary collaboration brings Mesoamerican potsherds and ruins to life

By Steven Schultz

|

|

|

|

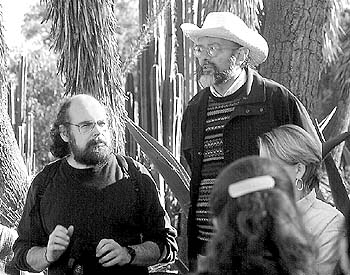

Davíd Carrasco (l) in Teotihuacan with

archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma

|

It's not the academic stereotype, but neither is Carrasco's approach to studying Mesoamerica, the portion of Central America that developed one of the world's first clusters of great cities, the Aztec and Mayan civilizations. Carrasco, professor of religion, has developed an imaginative way of looking at these cultures that breathes life into pottery shards and ancient ruins. According to other scholars in the field, this vision could change the way that US and European societies view Mexican and Hispanic cultures today.

"Davíd has done a tremendous job of making people aware of these cultures," says Charles Long, who was Carrasco's thesis adviser at the University of Chicago. According to Long, Carrasco has done more to improve understanding of Mesoamerican culture than many museums. Those institutions, Long says, tend to present artifacts as historical objects, without the active meaning that is part of Carrasco's work. "They don't have that existential oomph."

Ethnographers, astronomers

Carrasco's appointment is in the Religion Department, but he has devoted his career to cutting across traditional barriers between academic disciplines and helping colleagues in many fields work together. He is the director of the Mesoamerican Archive and Research Project, an affiliation of archeologists, anthropologists, ethnographers, historians, religious scholars and even astronomers.

They are the subjects of the 3D photo, from a 1989 conference at the Great Aztec Temple of Tenochtitlan, where the scholars were comparing modern stereographic pictures of Maya temples similar to pictures taken 100 years earlier. The 3D glasses made for an amusing moment, but the real wonder was that all those people were in the same room. Collaboration is the essence of Carrasco's approach and "the result has been an engaging and phenomenally productive exchange, with concrete results," said William Fash, chair of Anthropology at Harvard.

The archive's work also benefits from collaborations with researchers in Mexico. "American scholars are always going to someone else's land and digging up stuff and rarely talking to anyone there," says Long. "Davíd has brought together a tremendous collaboration between US and Mexican scholars." Among those collaborators is archeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, whom Carrasco calls a "national treasure of Mexico."

Emotional response

Carrasco grew up in Washington, DC, where his father David was the first Mexican-American to coach basketball at a major university, American University. When his father became a sports goodwill ambassador to Mexico as part of the 1968 Olympic games, the family moved to Mexico City, where Carrasco spent his teenage years. It was a trip to a Mexico City museum that started him thinking about the way Mesoamerican culture was portrayed.

"I remember coming out of the museum and having a strong emotional response, and a strong ambivalence," he says. "I had been indoctrinated by US culture to feel ashamed of Mexican civilization compared to European civilization. I felt that was a lie; there was something to be understood, there were intellectual issues."

That personal feeling for the subject helps Carrasco show how Mesoamerican cities, monuments and objects were interwoven in real lives, says Long, who is now retired from Duke and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. "It's a problem of knowledge, but it's also a question of existential meaning and identity."

Understanding sacred places

Later, at the University of Chicago, Carrasco became interested in the Spanish Conquest, which he describes as "one of the great dramas in history." He also began to think about the role religion played in the formation of cities and the way a culture's religion can be revealed through an understanding of its sacred places.

Carrasco points out that there are only seven places in the world where village populations independently coalesced into cities: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Northern China, the Indus Valley, Southwest Nigeria, Peru and Mesoamerica. What are the economic, intellectual, social changes that had to take place for the cities to develop?

"It was the religious ideas that really integrated all these things," Carrasco says, noting that the people at the top were always priest-kings. "That cosmological vision was needed to bring their calendars, their architects, their artists, their warriors into an integrated system."

The hearts of many of these cities were magnificent ceremonial monuments, such as the temples of the sun and moon at Teotihuacan and the Great Temple in Mexico City. Recently Carrasco has been developing a way of looking at these cities not just as fixed ceremonial centers but as fluid locales that export power and rituals to the surrounding countryside, which, in turn, helps shape the city itself.

Order in flux

In a 1991 article, "The Sacrifice of Tezcatlipoca: To Change Place," Carrasco looked at one important Aztec ritual of human sacrifice and showed how it transcended conventional notions of place. In this ritual, the community leaders selected a prisoner warrior and anointed him as a god for a year. The man was chosen for his good looks, dressed in luxurious clothes and treated like royalty. He was paraded through the city and around the surrounding country, and at then at the end of the year he was sacrificed on a nearby mountaintop.

Carrasco says that such rituals, with their movement through space and time, help answer a basic question: How do human beings in the flux of life find order and stability?

When Carrasco asks questions, he's good at getting others to think hard about the answers. A tall, solid man with a full beard and a mane of curly hair that reaches to his shoulders from the edge of a bald crown, he approaches conversations with a gregarious intensity. He has been master of Mathey College since 1994.

Graduate student Scott Sessions followed Carrasco to Princeton after studying with him in Colorado. "His approach to religion -- and scholarship in general -- is fascinating," says Sessions, who plans to finish his dissertation this year on the Spanish missionary project in the Americas. Sessions' research reflects Carrasco's goal of integrating a variety of intellectual questions in a single subject. Like much of the archive's work, it is relevant to understanding current issues, Sessions says. "The complex cultural situation we now face in the United States, in fact throughout the Americas, is rooted in the powerful and painful encounters between Africans, Europeans and indigenous peoples. The colonial period had a profound influence on the way the world is today."

Star of first magnitude

Some of the ideas generated within the archive are beginning to attract interest in other areas of research. For example, Philip Arnold, who studied under Carrasco at Colorado and is now an assistant professor of religion at Syracuse University, says he is working with the archive and scholars in Japan to gain a better understanding of "the meaning of urban space in the Pacific Rim."

Carrasco started the archive in 1984 when he was at the University of Colorado and brought it with him to Princeton in 1993. The archive provides funding for some archeological work in Mexico and maintains a collection of 12,000 slides of artifacts and ceremonial sites, as well as a library of 3,000 books, articles and conference papers.

In addition, the archive hosts regular conferences. The most recent, "ReImagining Mesoamerica: Archive, Community and Interpretation," was held at Princeton on April 9 and 10 and featured two presentations on new archeological finds at Teotihuacan and the Great Temple. The archive also produces numerous books and papers. "Judged by the standard of its publication record, it has shown like a star of the first magnitude," archeo-astronomer Anthony Aveni told participants in the April conference.

Carrasco is involved in a number of projects, including a screenplay about the conquest of Mexico with actor Edward Olmos and director Robert Young. He was recently asked to be editor in chief of the forthcoming "Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures," which will contain more than 500 articles from authors around the world.

In all these publications, the real power of Carrasco's work seems to be in inspiring new ways of thinking Says Fash, "This is precisely the kind of collaborative, crossfields perspective essential to real progress in our understanding of a time and place that are in many ways quite distant from our own but have much to teach us about humankind and the power of ideas, in a universal sense."