Princeton Weekly Bulletin May 10, 1999

27 volumes -- and 20 more to come

By Caroline Moseley

|

|

|

|

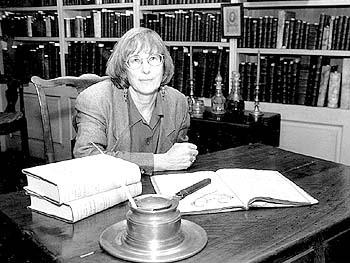

Barbara Oberg in the 18th century room at Firestone

Library (photo by Denise Applewhite)

|

"The Jefferson Papers was the nation's first major project in modern historical editing," says Barbara Oberg, newly appointed editor of the papers. "It has set the standard for the editions of the papers of the nation's other founders."

The massive project was initiated in 1943 on the occasion of the bicentennial of Jefferson's birth. Under the auspices of the History Department, the Papers has been divided into two series: chronological and topical.

"The chronological series," Oberg says, "is intended to present the estimated 18,000 letters Jefferson wrote, the more-than-28,000 he received, and the substantial body of memorandums, notes, reports, messages and travel journals that also came from his pen. The topical series includes his Extracts from the Gospels, legal papers, parliamentary writings and miscellaneous works."

The first volume in the chronological series was published in 1950. To date, the project has published 27 volumes in that series (as well as five in the topical series). "We've seen Jefferson through his 1793 resignation as Secretary of State under Washington," says Oberg. "Volume 28 will begin with George Washington's acceptance of that resignation, written 'with sincere regret' on New Year's Day, 1794." Other early letters in the upcoming volume will show Jefferson "happily heading off to Monticello," says Oberg. For example, he wrote to James Madison, who had sent him some Philadelphia newspapers, "I believe that I never shall take another newspaper of any sort. I find my mind totally absorbed in my rural occupations."

Despite Jefferson's declaration in another letter that "My private business can never call me elsewhere, and certainly politics will not," he went on to serve a term as vice president under John Adams and two terms as president of the United States -- and, in the process, to generate many more papers.

Oberg estimates that the papers covering the period from 1794 to the end of Jefferson's second term in 1809 "may fill 20 more volumes."

1760 to 1826

The office of the Papers on C-floor of Firestone Library houses shelf after shelf of brown folders, each one containing a photocopy of a document -- a total of about 60,000 documents drawn from 900 repositories in this country and abroad. Major repositories of original Jefferson documents, Oberg notes, are at the Library of Congress, Massachusetts Historical Society and University of Virginia.

The Papers' earliest holding is a letter written by Jefferson on January 14, 1760. "He was 16 years old at the time," Oberg notes. "He wrote to John Harvie, one of his guardians, and spoke of his desire to go to the College of William and Mary, where he hoped to study Greek, Latin and mathematics."

The collection's final letter is dated June 24, 1826. In it, the 83-year-old Jefferson sent his regrets to Roger Weightman, mayor of Washington, DC, in reply to an invitation to attend an Independence Day celebration. That July 4 turned out to be the day Jefferson died.

Humanities laboratory

While the project aims at comprehensiveness, the goal of publishing every relevant document is elusive, as additional documents continue to surface -- usually, says Oberg, in private collections. Recently, for example, "A letter came in from an autograph dealer in Kew Gardens, NY. It's a letter from Jefferson to the architect William Thornton and deals with a book Thornton had loaned him. It's dated January 11, 1809, at the very end of Jefferson's presidency."

Besides Oberg, the project staff consists of associate editors James McClure and Elaine Pascu; John Little, research assistant; and editorial assistants Stephanie Longo and Linda Monaco. Oberg, dedicated to "collaborative scholarship in the humanities," compares the operation of the Papers to "a scientific laboratory, where everyone works together."

One of the major tasks of the edition is annotating the volumes.

"We don't just establish the text of a letter," Oberg points out. "We also provide explanatory material -- information that makes the letter understandable." One of the many editorial decisions discussed by the staff is what should be annotated and what should not. "If George Washington is mentioned," says Oberg with a smile, "we don't feel the need to identify him." But what about Tench Coxe, a political economist from Pennsylvania? "We go the extra mile for someone whose name is not a household word," she says.

The question of how to proceed with annotatation calls for further discussion. When that same Tench Coxe refers in a letter to a pamphlet he has written, Oberg says, "We'll talk about how we can find out what the title of the pamphlet might be. What contemporary newspapers might we look at or what bibliographies?"

Other typical questions are "Shall we print a particular supporting document in its entirety or shall we summarize it in a footnote? If a document is undated, how can we establish a likely date? If a letter is in French, shall we translate it?"

Monticello Foundation

Last December the University and the Monticello Foundation agreed that, while Princeton will retain responsibility for the chronological series through Jefferson's presidency, and for the topical series, it will transfer to Monticello the responsibility for editing Jefferson's retirement years (1809-1826). Oberg will continue as general editor of the series, and all volumes will be published by Princeton University Press. "This arrangement will make Jefferson's papers accessible at the earliest possible date," Oberg says.

She notes also that an electronic edition of the Papers will eventually be available on CD-ROM, to ensure wide access to the documents.

Today's editor must concern herself with more than words, in whatever medium. Oberg is also responsible for writing grant applications on behalf of the Papers and seeking continuing support from government agencies, foundations and individuals. To date the project has been supported by a combination of public and private funding.

12 years of Franklin papers

A graduate of Wellesley College, Oberg received MA and PhD degrees from the University of California, Santa Barbara. A documentary editor for most of her professional life, she was editor of The Papers of Benjamin Franklin at Yale University for 12 years before coming to Princeton. "Jefferson is like Franklin in many ways," she observes. "Both are scientific, imaginative, involved in politics and with a wealth of other interests." Always "fascinated by Jefferson," she was drawn to Princeton by the presence of the Jefferson papers and "the excitement of being a part of Princeton's History Department."

In addition to serving as editor of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Oberg holds the title of lecturer with the rank of professor in history. A historian of the colonial period and the early Republic, she will advise junior and senior independent projects and teach seminars at all levels, according to department chair Philip Nord.

Believing that The Papers of Thomas Jefferson "should be open to all people with serious research interests," Oberg urges students, faculty and other scholars to visit the Papers and make use of the documents, the library of Jefferson-related material and the expertise of the resident staff.