Princeton Weekly Bulletin May 3, 1999

Senior searches for anxiety genes

By Steven Schultz

|

|

|

|

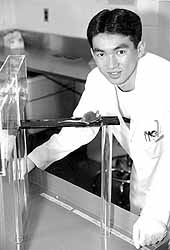

Toshio Kimura with mouse on anxiety-provoking,

unrailed segment of maze

|

That's not because of the two weeks he spent holed up in his room not talking to anyone or the two hours of sleep he got in the last days before it was due. It's because he discovered a possible genetic basis for anxiety.

Kimura used strains of anxiety-prone mice to show that there are aspects of their genetic makeup that may induce their reaction to stress. Although he did not discover the precise gene or genes responsible for anxiety, his thesis, "Characterization of Anxiety-Related Behavior and Associated Quantitative Trait Loci in Inbred Mice," did identify sections of DNA that might be responsible for the behavior.

"For an undergraduate thesis, it's fantastic," said Kimura's adviser, molecular biology professor Lee Silver. "It's very tantalizing."

Some relaxed, some nervous

Kimura, who first met Silver in a freshman seminar, started his gene-search project for his junior paper. His first step was to measure the level of anxiety in several strains of mice. He used a maze that contains an open area where the mice don't like to be; the length of time they are willing to explore that spot reflects their level of anxiety. One strain appeared relatively relaxed, and two were real Nervous Nellies. Kimura then performed a series of crossbreeding experiments and produced a strain in which there was an even distribution of relaxed and nervous mice.

Observing DNA

In his senior thesis he compared the genetic makeup of the most nervous and most relaxed mice. Fortunately, the original strains had unique bits of genetic material, or markers, between their genes that identified them as a member of their particular strain. During the crossbreeding, each offspring mouse aquired patches of genes from one parent strain or the other, in a random distribution.

Kimura looked at the more relaxed mice and identified which parts of their chromosomes came from the relaxed parent strain. The presumption was that these sections of DNA must be the ones that contain the genes for relaxed behavior. He then looked to see how many of the stressed mice had the same sections of DNA from the relaxed parent strain. There turned out to be just two sections that occurred much more often in the relaxed mice than the stressed ones.

Silver, whose research focus is the genetic basis of behavior, said Kimura's work not only points the way toward a gene for stress, but also toward a gene that promotes a novelty-seeking trait.

As a final piece of research, Kimura looked up what genes already were known to be within these two sections of DNA. It turned out that scientists testing drugs on mice already believed that some of these genes were involved in anxiety. When scientists do drug tests, however, they are never completely sure if their drug is acting on the root cause of the behavior or causing an indirect chain of events. Genetic tests such as Kimura's are more likely to identify the natural underpinnings of a particular characteristic, he says.

Public health

After all that work, what of Kimura's own reaction to stress? He jokes that many stressed friends volunteered to be research subjects, but he doesn't put too much pressure on himself. Nevertheless, he's ready for a break. "I think I want to stay away from the lab for a while," says Kimura, who went to a math and science high school in Chicago. "I want to step back and do something different."

And he knows what. Even more than his research, he says, his most formative experiences at Princeton came when he traveled abroad to do health-related volunteer work in Third World countries. He worked in a refugee camp in Thailand and a hospital in Haiti and spent three months in Kenya developing an HIV prevention and education program. These experiences gave him an interest in international health issues, so he now plans to do a yearlong internship with the World Health Organization in his native Japan. After that, he plans to attend the Yale University School of Public Health and study international health.

"I think ultimately I'll enter medical school and revisit molecular biology as a consequence, but for the time being I want to take some time off from the sciences and pursue other interests," he says.