Princeton Weekly Bulletin April 5, 1999

Culture of coffee, "syrup of soot"

By Maria LoBiondo

|

|

|

|

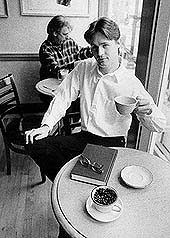

Brian Cowan |

In studying the origins of coffee's popularity and the complexity of London's coffee trade and its coffeehouse culture, he examines the cultural processes that shaped early modern capitalism into a complex global system of market exchange.

The coffeehouse "was a London phenomenon. London had more coffeehouses than all of Europe, except Constantinople," says Cowan, over a cup at Small World, his Princeton coffeehouse of choice. "In the pre-office age, coffeehouses were places where business could be accomplished." They were bustling, noisy place where merchants, quack doctors and newspaper-hawkers came and went to do their business or sell their goods.

Like their modern counterparts, specific 17th-century coffeehouses attracted specific clientele. Lloyds, for example, was the precursor of the insurance brokerage firm Lloyds of London. Garraway's and Jonathan's, known for the businessmen who frequented them, helped give birth to the London Stock Exchange.

Virtuosos promoted coffee

What attracted Cowan to his subject (besides, perhaps, warm memories of espresso bars that dotted Portland, Ore., during his undergraduate days at Reed College) was the chance to do cultural, political and economic history while researching a single commodity.

"Where does demand come from? Why do people want the things they buy? While doing research, I found I really had to pay attention to language and think about what people were saying, using the tools of intellectual history, to answer the questions I had," Cowan says.

On two separate trips to England to research the trading practices of the East India Co., he was surprised to discover that the real force behind coffee promotion was initially not business but pleasure.

During the Restoration period, upperclass gentlemen developed what Cowan calls a "virtuoso community" that was key in promoting coffee drinking. The virtuosi shared a common sensibility they called curiosity (a term of high praise). They studied and collected natural history objects such as shells or skeletons, objects of art and anything exotic--which coffee was then. The virtuosi invented the coffeehouse as a social institution, Cowan says, replacing the great house, where they had socialized exclusively before this time.

Once the idea of the coffeehouse was introduced, it moved beyond its upper class circle into London's urban culture, and coffeehouses became numerous in the city. They offered their customers the chance to experience a fantasy of indulgence by imbibing exotic drinks (including hot chocolate and tea), and they legitimized this extravagance by advertising the virtuoso belief that those drinks had medicinal properties, Cowan notes.

What's more, although divisions of class, gender and religion continued to fragment metropolitan society, the coffeehouse offered a place with more accessibility than existed previously. Coffeehouses provided a central spot for gathering news and exchanging views in the days before mass communication.

Essence of old shoes

There were those who decried coffee drinking, calling the "syrup of soot or essence of old shoes" unhealthy, but the 17th-century medical establishment came out in favor of coffee's stimulant properties, Cowan notes. Eventually, however, tea won out over coffee, at least in the British Empire, for at least two reasons: by the 1720s the Dutch had smuggled coffee plants out of Arabia and began competing for coffee trade, and the East India Co. developed a more secure tea trade route with China.

Cowan contends that ultimately the main connection between the coffeehouse phenomenon of the 1600s and the 1990s is that both are products of the consumer culture of their respective eras. "All historians' agendas are ultimately shaped by their surroundings," he says. "They take their interest and use it to explore radical differences with the past."

Cowan expects to complete his work on "The Social Life of Coffee: Commercial Culture and Metropolitan Sociability in England, 1600-1720" this year with the help of a Capitalism and History Research Fellowship. He received the $15,000 award, offered biennially to a scholar studying business in North America or Western Europe between 1600 and 1950, by competing with 19 others from as many universities. Funded by the Thomas Doerflinger Foundation, the fellowship is given to projects that both illuminate the money-making efforts of firms and address important historical projects.