Princeton Weekly Bulletin March 29, 1999

Numbers: not whole story

Graduate student assesses long-term effects of poaching on elephant society

By Caroline Moseley

|

|

|

|

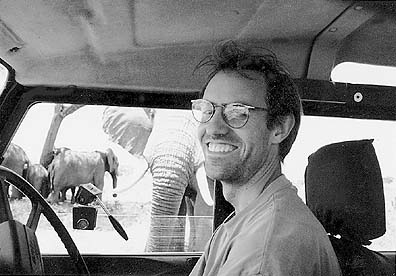

Charles Foley and research subjects

|

Foley, a graduate student in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology now doing field work in Tanzania's Tarangire National Park, studies the long-term effects of poaching on elephant society.

To understand "the whole story," he explains, "you have to know a bit about elephant social structure. Elephants are very social animals; they live in a matriarchal society in which the old female is the leader of a family group consisting of her daughters and their offspring." They will stay in a family group for life, he says, "with very strong social bonds and high levels of altruism." Male elephants leave the family group early and return to the female groups only to breed.

The matriarch makes decisions for the group about where to go to get food and water and how long to stay there. The old females are a repository for information about habitat. They remember, for example, where they can go to find water during a drought. "The group may not have been there for 30 years," says Foley, "but a female will remember where her grandmother took her."

What poachers want is the biggest tusks, Foley points out. Sinces males have bigger tusks than females, and tusks grow throughout life, "Poachers go after the oldest males first. By the time they get down to males in their 20s, the tusks aren't much bigger than the older females, so the poachers start targeting the oldest females." In some heavily poached populations, "You've lost all your males over 25 and most females over 35. It's kind of a Lord of the Flies scenario: What happens if you remove all the adult population?"

All-out attack

A dramatic rise in the market value of ivory in the early 1970s caused "an all-out attack on elephants," Foley says. When the price "suddenly went up from about $5 per pound to about $60 per pound, the tusks of a large male elephant could bring in $50,000." Poachers killed the elephants and sold the tusks to a middle man, a trader who exported them to Asia, Europe and the US, where "the ivory was made into trinkets or stored as bullion," Foley says.

At that time the trade was legal, sanctioned by CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Foley explains. Then, as "the elephant population of sub-Saharan Africa crashed from 1.2 million to about 600,000 (Kenya, for example, lost 90 percent of its elephants)," conservation organizations began to demand a trade ban.

In 1989 CITES voted to ban trade on all elephant parts. Overnight, "The value of ivory plummeted because there were no buyers -- so poachers stopped killing elephants," says Foley.

Home to 2,000 elephants

The 1000-square-mile Tarangire National Park is now home to about 2,000 elephants. Elephants who lived outside the park and were severely hunted during the poaching years emigrated into the park and stayed there. Other family groups, who lived in Tarangire all along, were protected from poaching.

Thus, the park offers an opportunity to compare normal family groups with the poached, altered family groups, Foley points out. Part of his work is to identify individuals and then family groups. Individual elephants can be identified, he says, "by looking at their ears. They have notches, rips and tears that tend to be recognizable, and all have different venation [blood vein] patterns."

Foley "expected that the altered families, by having lost the matriarch who knew her way around their environment, would be at a disadvantage," he says. But findings to date have been mixed. So far, it seems that overall the altered families have about the same pregnancy and infant survival rates as the normal families.

The real differences are seen between different elephant clans -- family groups that share the same dry season range, Foley says. During a severe drought most family groups left the park. Some family groups, though, stayed behind, and these suffered significantly more infant mortality than those that left. "The groups that stayed all belonged to one clan that only had one female over 30," Foley notes. "The other clans had several family groups with a full complement of older females. The groups that remained in the park either didn't know where to go because their matriarch was relatively young -- or perhaps the other elephants excluded them from resource areas."

Poaching effects masked

These findings, he says, suggest that "the effects of poaching are probably long-term and may well be masked in years when there is a plentiful food supply and all animals can thrive."

In addition, "Elephant social structure is extremely complex. There may be a higher level of interaction than family groups; certainly, interactions between family groups are fairly important. The groups with young matriarchs may have followed the old matriarch to areas where there is food and water. Females from poached groups might be at the bottom of the heap -- the last ones to get a drink of water -- but still receive some level of protection from older females."

Foley plans to continue studying the long-term effects of poaching on elephant social structure. He will also track the movement of selected elephants outside the park -- where it is harder to make direct observations -- via radio collars with attached GPS receivers.

Living in a tented camp in the park with his wife and fellow researcher Lara, assisted by two Tanzanian staff, he plans to spend several more years in the park, "recording elephant interactions and monitoring the elephants' reproductive success, and how they respond to stresses in the environment." Support for the enterprise comes from his department, the Wildlife Conservation Society and the African Wildlife Foundation.