Princeton Weekly Bulletin March 1, 1999

That was one of the things about the end of the war.

Absolutely anybody who wanted a weapon could have one. They were

lying all around.

--Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse Five

Practical solutions

|

|

|

|

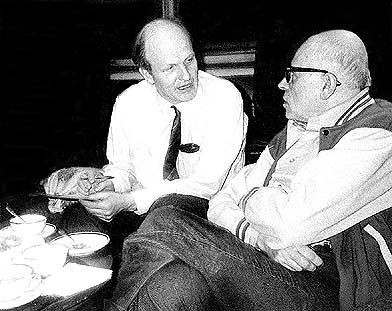

Frank von Hippel (l) with Andrei Sakharov. "The

photo was taken in Sakharov's apartment in January 1987,

just after Soviet President Gorbachev allowed him to

return from a 7-year exile in Gorki," says von Hippel. "A

few days later, Sakharov had his first meeting with

Gorbachev, which I attended. Sakharov played a leading

role in the development of the Soviet H-bomb in the 1950s

and later became Russia's leading human-rights activist,

for which he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975."

|

By Peter Page

Disarmament policy analyst Frank von Hippel finds Vonnegut's observation apt in the aftermath of the Cold War. In the economic rubble of Russia, the scientists and technicians who built the Soviet nuclear armory are as poorly and infrequently paid as factory hands, despite the temptation to peddle their skills and pilfered plutonium to rogue states and aspiring nuclear powers.

"There have been two miracles in the last half of this century," observes von Hippel, "First, we haven't had a nuclear war. The second miracle, the one we're in the middle of now, is that there has not been a hemorrhage of nuclear material and talent during the collapse in Russia."

Over the past 25 years, von Hippel's work as an analyst has focused on re-ducing the world's reliance on miracles. Professor of public and international affairs, he codirects the Research Program on Nuclear Policy Alternatives with senior research policy scientist Harold Feiveson at the Center for Energy and Environmental Studies (CEES). "We're working in areas that are largely unexplored," von Hippel says. "Here, for the first time, we're laying out the technical basis for nuclear arms control."

Avoiding nuclear disaster, he believes, requires practical solutions to specific problems. Among current projects of the research program, he highlights efforts toward the following:

• taking U.S. and Russian nuclear missiles off "launch on warning" postures;

• helping Russia's nuclear weapons complex convert to civilian nuclear missions;

• a verified global ban on the production of fissile material for nuclear weapons; and

• verified elimination of U.S. and Russian excess nuclear warheads.

Launch on warning

Any sense that the risk of nuclear war ended with demise of the Soviet Union is exaggerated, von Hippel warns. Nuclear weapon arsenals built during the long ideological struggle between the superpowers remain ready for use a decade after the Soviet Union dissolved. The United States and Russia each have 2,000 warheads ready to launch on 15 minutes' notice, a posture known as "launch on warning."

While the threat of a deliberate attack has faded, the possibility persists that a technical or human error could trigger an exchange of missiles, von Hippel points out. He cites an incident in January 1995, when a research rocket launched from the Norwegian island of Andoya was mistaken for a submarine-launched nuclear missile by Russian air defense forces. The "nuclear suitcase" held by Russian President Boris Yeltsin was activated, and a decision to launch a counter-attack was minutes away before the blip on Russian radar screens was judged harmless.

To prevent such near misses, Von Hippel is working with Bruce Blair of the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., on proposals to remove the trip wire from both U.S. and Russian missiles without making either side vulnerable to a surprise attack. Outlined in "Taking Nuclear Weapons off Hair-Trigger Alert" (Scientific American, November 1997), these proposals would establish a situation "where it would take hours to launch a missile instead of minutes," von Hippel notes. "That would be an improvement."

Nuclear cities, verified bans

Von Hippel believes that helping Russia's nuclear cities convert to civilian activities is crucial to strengthening the security of the Russian nuclear stockpile. The Nuclear Cities Initiative, which creates employment for technicians and scientists, was described in "Retooling Russia's Nuclear Cities" (Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, Sep.-Oct. 1998). Proposed in 1997, the program is federally funded this year at $30 million. As "key collaborators" in this effort, von Hippel cites senior visiting fellow Kenneth Luongo, research staff member Oleg Bukharin, Matthew Bunn of Harvard's Kennedy School, and Jill Cetina, who earned an MPA at the Woodrow Wilson School and now works in the U.S. Treasury Department.

A verified global ban on the production of fissile material for nuclear weapons and verified elimination of U.S. and Russian excess nuclear warheads are projects von Hippel and colleagues have worked on for many years. The former, he says, was "an old proposal we revived in the 1980s"; the latter is "a proposal for which we laid the initial technical basis in Reversing the Arms Race: How to Achieve and Verify Deep Reductions in Nuclear Weapons, a U.S.-Soviet book published in 1990." Both proposals are actively on the table now. Multilateral negotiations on a fissile material ban "are about to begin at the U.N. Conference on Disarmament in Geneva," von Hippel says, and elimination of excess nuclear warheads is "on the U.S.-Russian negotiating agenda."

Analysts' role

For a decade after taking his PhD in theoretical physics at Oxford University in 1962 von Hippel followed a conventional path of teaching and research.

"I was probably among the top 10 percent of theoretical elementary particle physicists," he says, "but all the action was in the top one percent. I didn't feel I was making enough of a contribution."

In 1969, while finishing up a three-year stint as assistant professor at Stanford, he made his first foray into what he calls "public interest science." He agreed to serve as faculty adviser to a student group trying to understand why scientific advice was not having more impact on such decisions as whether the United States should build an antiballistic missile defense.

Von Hippel came to Princeton in 1974 as a senior research physicist at CEES, where, in the late 1970s, he and his colleagues turned their attention to the nuclear-proliferation dangers of plutonium breeder reactors. These reactors were being trumpeted as the energy source of the future because of the plutonium they yielded as a byproduct of generating electricity. The CEES research group calculated that a global "plutonium economy" would annually yield enough plutonium to build a virtually unlimited number of nuclear bombs.

When President Ronald Reagan took office, with his talk of the Soviet "evil empire," von Hippel turned his full attention to the nuclear arms race. He sought ways to make the disarmament envisioned by activists seem feasible to a national security establishment that viewed disarmament proposals as either impossible or reckless.

The analyst's role, he explained, is to devise the technical means that will convince military leaders--both in the United States and in Russia--that their national security will be enhanced, not reduced, by what diplomats call "transparent and irreversible reductions" in nuclear weapons. Von Hippel has been asked to facilitate the background discussions that will launch U.S.-Russian negotiations in this area.

Von Hippel's only experience working inside government was a brief stint as a science advisor in the Clinton Administration during 1993 and 1994. He was frustrated by the avalanche of faxes, e-mail and phone calls and by the sense of skipping from crisis to crisis. But he acquired a clearer understanding of the pressures facing decision makers.

"When you're inside the government you don't have time to think," he said. "People like me, who are on the outside, set the agenda. We can't make the decisions, but we can give the decision makers ideas."