Princeton Weekly Bulletin, March 23, 1998

Freshman discovers household disinfectants promote bacteria resistant to antibiotics

Germ warfare

By JoAnn Gutin

Who says television rots your brain?

Five years ago, Merri Moken '01 was watching TV when she happened to see commercial for a household cleanser, and the experience changed her life. Inspired to investigate the advertiser's claims, 13-year-old Moken embarked on what became thousands of hours of independent scientific research.

|

|

|

|

|

Two months ago she published her findings in a scientific journal; within the past few weeks, she's been featured as a scientific phenom by media both here and abroad. But most importantly, Moken has made what could be a significant scientific discovery: she's the first person to document the scary fact that by using common household disinfectants we're creating strains of mutant, antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Truth in advertising

The ad that triggered this five-year cascade of events featured cartoon "scrubbing bubbles" that dramatized how squeaky clean the product left your kitchen. Moken wondered if the advertiser was telling the truth.

"I got to thinking," she recalls. "They made everything look so perfect -- but how could you be sure disinfectants worked against harmful agents like bacteria?"

Moken undertook her first set of experiments for her ninth grade science fair. After treating bacteria-infested gel plates with various pine oil disinfectants, she measured the area of dead bacteria. She found that some disinfectants were very effective for up to 24 hours, and others weren't. (The bubbles cleanser was one of the effective ones.)

But she also noticed something else: at 48 hours the bacteria would come roaring back. Because disinfectants and antibiotics kill germs in similar ways (by breaking down the bacterial cell walls or inhibiting protein synthesis), it occurred to the budding researcher that the colonies of bacteria she saw within some of the zones of inhibition around some of the disinfectants might be mutant strains, and they might be resistant to antibiotics as well as to disinfectant.

Till three in the morning

Though the average ninth-grader finds Brad Pitt more attractive than E. coli, Moken says, "I fell in love with my science project, and it became my life." By sophomore year she was growing four standard bacterial strains, plus her mutant strains. "I'd be up working on my project almost every night, often till three in the morning."

As the project got more ambitious, it required more equipment: a refrigerator, borrowed incubators, a borrowed spectrophotometer. Fortunately, Moken's parents, though not scientists, are tolerant people. "I started off in the breakfast room, but now I've expanded into the room next to the breakfast room," she confesses. "And the kitchen, actually. Just part of the counter, though -- not the whole thing."

By junior year, Moken had discovered that her hunch was right: the bugs were resistant to antibiotics. For the final phase of the project, she set out to characterize the genetic differences between her mutant bacteria and the original strains.

From her reading, she knew that some doctors at Tufts Medical School had isolated a gene, marA, that was over-active in antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Summoning up her nerve, she contacted the doctors and asked for some of their bacterial samples. Reaching out to others, she had found, was an essential tactic for the independent researcher. "You just have to hope people will be willing to help you," Moken says.

The Tufts researchers came through -- with time, supplies and expertise. And after another year of increasingly sophisticated analysis, Moken was sure an overexpressed mar gene accounted for the disinfectant- induced antibiotic resistance. Her Tufts contacts offered to repeat her work in their lab and to help her publish her paper, which appeared in the Journal of Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Says Dr. Laura McMurry of the Tufts microbiology department, "We've never had a high school student come to us with an idea we hadn't thought of before. I consider Merri a scientific colleague." Moken has impressed other people, too: she was selected as a Westinghouse Talent Search Finalist and as the Grand Prize Winner in Microbiology in the 1997 Intel Inter-national Science and Engineering Fair.

First person ever

The fledgling scientist has had to cope with more disasters than most established researchers. Someone once threw away a week's worth of her work that had been stored in a borrowed freezer, because they didn't think it belonged to anyone. Another time, the cold room conked out in a lab where she'd begged some space. All her DNA was cooked, and no one remembered to tell Moken, who had been away for several days visiting colleges. "I spent at least a week and a half trying to figure out why my experiments weren't working," she says ruefully, "until I ran DNA tests and found out there wasn't any."

But the struggle has been worth it. "I was the first person to ever find this!" Moken says delightedly.

The demands of freshman year at Princeton have meant putting her research temporarily on hold. She's been doing pre-med requirements and experimenting with courses like economics and philosophy.

"The thing is, I seem to be interested in everything," she says, half apologetically. "I love science and math, but I love art; I love to read; I love to write and play the piano. Oh, and basketball ... and Spanish. I love languages."

And what about the original source of her inspiration?

"Television? Oh, I never watch television here."

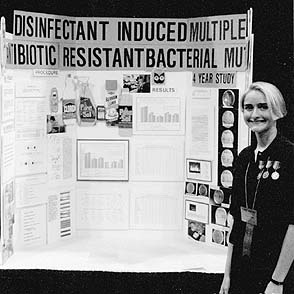

Moken as a high school senior with her exhibit at the International Science and Engineering Fair in Louisville, Ky.