From the Princeton Weekly Bulletin, February 9, 1998

How

many bricks

How

many bricks

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet teaches in Creative Writing program

By JoAnn Gutin

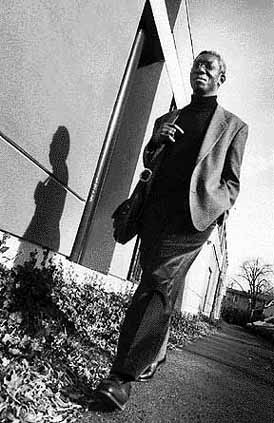

Photo by Denise Applewhite

In 1984, Yusef Komunyakaa found himself at a crossroads in life. Since the early '70s he had been knocking around the academic world, collecting one undergraduate and a couple of graduate degrees, assorted honors and the occasional fellowship. From 1980 on he had been teaching, but under fairly grueling and not especially fulfilling conditions: English Composition at a big commuter college; visiting artist in the public schools. But in 1984 Komunyakaa was offered a one-year position in the creative writing program at Indiana University.

Most people would have jumped at the chance, but not Komunyakaa. Now, sitting behind his desk in his immaculate, sunny office in 185 Nassau St., he recalls the dilemma.

"I had to decide whether to continue on the academic path or to follow in my father's footsteps and become a carpenter. And I thought, `If I become a carpenter, I'll have time for my real work.'"

Komunyakaa's real work is writing poetry. He decided to take the Indiana job, but not as a stepping stone to academic respectability. "I figured I'd do it for a year and make enough money to buy a good set of tools. And my father always said, `If you know the tools, you can do the job.'"

My father could only sign

His name, but he'd look at blueprints

& say how many bricks

Formed each wall.

Ten years later Komunyakaa was still teaching at Indiana, somehow having managed to produce eight books of his real work along the way. Then in April 1994 the phone rang in his office, and someone read to him from a press release: "Yusef Komunyakaa has been awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his poetry collection Neon Vernacular. "

Bogalusa, La.

Komunyakaa writes what the New York Times has called "fiercely autobiographical" poetry, much of it based on his childhood in the rural South and on his young manhood in Vietnam. Yet there is nothing fierce about his presence, and there was nothing that hinted of poetry in the family where Komunyakaa grew up. In fact, there were hardly any books in the house in Bogalusa, La., a sleepy mill town on the Pearl River 70 miles northeast of New Orleans.

Still, his life was not without literary influences. Komunyakaa read the Bible through, twice, when he was 16. His grandmothers were church people, and he thinks "the Old Testament informed the cadences of their speech. It was my first introduction to poetry." He also pored over the set of encyclopedias his mother bought him, one volume a week, in the A&P; and he checked James Baldwin's Nobody Knows My Name out of Bogalusa's black library 25 times.

Absorbing images

But the biggest influence on Komunyakaa's poetry and his life was the lush semitropical landscape around his house, where he ran free as a child.

"I like to think that even then I was noticing small details, absorbing vivid images," he says. "I used to go off by myself, just check things out. And I always wanted to know the names of things--the trees, the flowers, the insects."

I am five,

Wading out into deep

Sunny grass,

Unmindful of snakes

& yellowjackets, out

To the yellow flowers

Quivering in sluggish heat.

Bogalusa sounds like a child's paradise in these poems, but the place had a dark side. "It was a terrible place to grow up, really," he says. "The limitations in vocation, especially for black males. If I hadn't gotten out of there, I'd be the same person I am now, but...."

Though Komunyakaa's voice trails off, the meaning is clear. If he'd stayed in Bogalusa, the fledgling poet whose first literary effort was a hundred-line poem "in the style of Tennyson, full of lofty sentiments for the future," written for his high school graduation, would not now be sitting in a Princeton office awaiting publication of his ninth poetry collection in February, would not have a 500-page "Collected Poems" due out in 1999.

Combat reporter

Komunyakaa got out of Bogalusa the way young men have fled the countryside since Homer's time: he joined the Army. It was 1969, and he was shipped to Vietnam, where he wound up as a combat reporter for the Army newspaper Southern Cross. Assigned to the Americal division (the biggest division in the army, 24,000 men), he saw the battlefield when the smoke had barely cleared. "Whenever anything happened on the field, I was there in a helicopter to cover it," he says.

After Vietnam and a Bronze Star, it was the University of Colorado on the GI bill, where Komunyakaa discovered creative writing workshops and began writing in earnest. At first the poems were about Bogalusa, short, jazzy pieces with titles like "Woman, I Got the Blues" and "Copacetic Mingus."

It took him 14 years to write about the Vietnam experience, but when he did, the work gained him national attention. The collections Dien Cai Dau (Vietnamese for "crazy" and for "American soldier") and Magic City have been described as "infused with rage ... while invoking feelings of tenderness and hope."

You can hug flags into triangles,

But can't hide the blood

By tucking in the corners.

Since publication of those works, his poetry has become part of the modern canon, included in The Norton Anthology of Poetry and in successive editions of Best American Poetry.

"Ode to a Maggot"

Komunyakaa's current work is less incendiary, though no less emotionally charged. His habit is to work on three projects at a time. One of the current trio of works-in-progress is a series of 16-line poems about small, overlooked things, such as "Ode to a Maggot." He keeps a notebook but also jots images on whatever comes to hand: "I like to write on everything--backs of envelopes, bits of newspaper." Since coming to Princeton, Komunyakaa has taken to composing in his head as he walks to work, and often finds he's written eight fairly finished lines in the 45 minutes it takes to get from his house to his office.

He arrived in Princeton this past fall as professor in the Council of the Humanities to teach poetry and advanced poetry workshops in the Program in Creative Writing. When he starts teaching his courses in the spring, Komunyakaa says, he has a clear idea of what he wants to communicate.

"Students often have such a lofty idea of what a poem is, and I want them to realize that their own lives are where the poetry comes from. The most important things are to respect the language; to know the classical rules, even if only to break them; and to be prepared to edit, to revise, to shape."

The process reminds him of something he learned from his carpenter father. "Before he cut a board he'd measure it seven times, up and down, up and down. And then when he cut, it would slip right into place. Perfect. No light, left or right."

Sounds like a poem.